On the final day of Black History Month, it seemed like a good time for some reflection. Earl B. Gilliam Bar Association co-sponsored the International Women of Color Day presentation of Judge Sunshine Sykes last night hosted by Lawyers Club of San Diego. Judge Sykes is the first Native American woman to serve on the Riverside Superior Court. Having been to Tuba City (and seen the dinosaur tracks) where Judge Sykes grew up, I was thrilled to be present and hear from someone who had come so far in life. March 1st marks the start of Women’s History Month, and while I feel certain no one will feel the need to ask the self-evident question of why we need a specific month to honor women, it seemed fitting to do one last post to bridge the end of a celebration of African American accomplishments generally to celebrating women. To do that, let’s take a look at a practice that had a tremendous impact on African-American women and families well into the 20th century. You may be surprised…

Before I get started, though, I came across this incredible history of San Diego’s downtown that I never knew existed. It is a history whose story may not have been told but for a guy named Gil Johnson, who I have recently come to know as a very compassionate man interested in helping all San Diegans in the region get the most out of life. Here is the study:

Centre City Development Corporation – Downtown San Diego Heritage Study

If you have a moment to read, a few highlights of what you’ll find include

Learning about the Howard “Skippy” Smith parachute building on 8th avenue and what role an African-American man played in helping aid an historic effort in World War II.

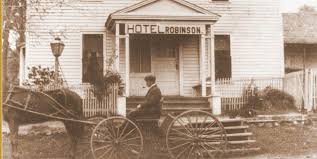

You’ll read about how Julian (perhaps best known for its pie – and more recently its San Diego Craft Beer with Nickel Beer Co.) was a welcoming place for African-Americans in the 19th century and led Albert and Margaret Robinson to start a hotel called the Robinson.

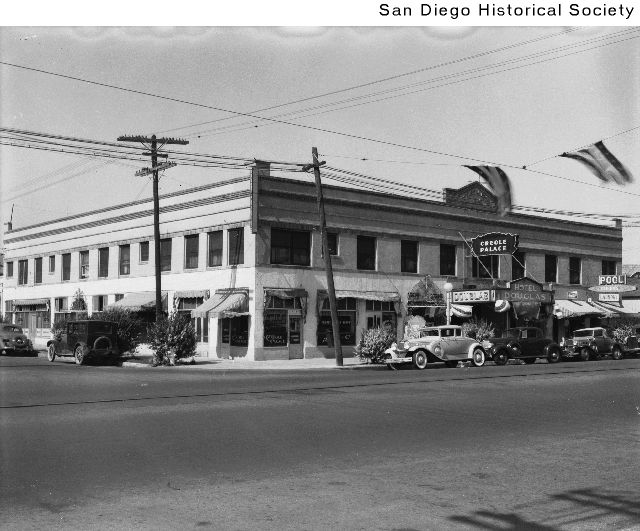

And even about George Ramsey’s New Douglas Hotel, which cost $100,000 to build (roughly $1.3MM in today’s dollars)

But let’s move on to the important, if quite somber, topic that started this post. Often we hear people make comments about how slavery ended in 1863 (or later if you were a slave in Texas) and it doesn’t make sense to “dwell” on it 150 years later. I’m not much for dwelling on 150 days ago, let alone 150 years, but perhaps there is more to the story than that.

Black History: digging a little deeper

Being a Generation Xer, I grew up with the stock tales of American Black History: slave ships, Crispus Attucks, the abolition efforts of Fredrick Douglas, the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation, the Freedom Rides, the Civil Rights Act, the life and death of Martin Luther King and, if I was really lucky, a nod to Shirley Chisholm. I vaguely remembered hearing about sharecropping and Jim Crow, but it was never covered in any depth. Then I was watching Lee Daniels’ The Butler recently and there is a scene in which a “free” Black man was shot for having the temerity to object to his wife’s rape by the owner of the farm on which he was sharecropping. I wondered if there wasn’t a more compelling story to share.

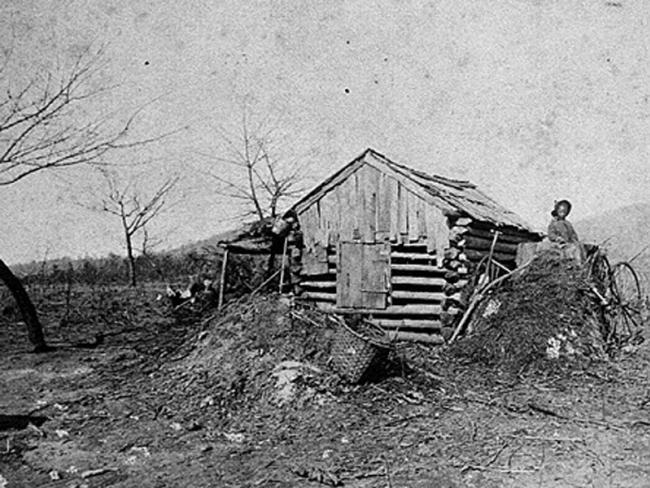

First, let’s get a basic understanding of what “sharecropping” actually was. The basic principle – and the way I was taught it in school, actually – was that southern land owners would lease land to former slaves and the lease payment would take the form of a share of the crop, hence the name. Here is a fascinating explanation from the state of Georgia. A few points worth noting to analyze this practice:

- Many southern states – where sharecropping was practiced – didn’t allow Blacks to learn to read even after the Civil War. How exactly does one negotiate a contract in this context?

- Imagine the implications of compound interest for people who never learned what it is until being charged it as part of their “share” of a crop.

- Consider the implications of a legal and social system (read: what was Jim Crow) that didn’t care if you couldn’t read, wouldn’t protect your property rights and made taking your life far less than a capital offense in practice.

- It didn’t end until at least 1960…yes, you read that right.

With this as backdrop, it hopefully puts the context of the “shared crop” into focus a bit. This piece helps highlight the importance of finally having access to education.

But the really important take home messages require answering a few simple questions. These include:

- Do you know anyone born before 1960?

- Do you have friends or family raised by people who were born before 1960?

- Did you grow up knowing how to read proficiently?

- Did your parents have access to a quality education in math and language arts?

- Do you know anyone who can’t use the legal system to enforce a contract?

Now imagine for a moment that, like Forest Whitaker’s character in The Butler, your parents weren’t allowed to read, add or subtract. And imagine what impact it might have had on your parents to watch each other be dehumanized by their sharecropping “business partner.” And imagine that this wasn’t 150 years ago, but 50 years ago. If your parents lived that life, would you be equipped with the tools to raise well-adjusted children? Would you have grown up with a passion for education and the advancement it might bring? The next time someone ponders the effects of “ancient” history, you’ll know that it wasn’t like the really bad stuff just stopped when the news finally made it to Texas in 1865.

The purpose of this post isn’t to dwell needlessly on a system that no longer exists. America and the people who call her home present tremendous opportunities today. Many people I know have transformed their lives and the future for their families through the bounty and opportunity that hard work and sacrifice can make possible in this country. And many people who work hard and sacrifice are nevertheless unable to take advantage of that bounty. This post helps place some of the struggles in a historical context. And it helps highlight the importance of leaders in the legal community in ensuring that civil, human and property rights receive protection under the law.

Recent Comments